Jan 23, 2026

In many industrial systems, a 2 way solenoid valve is not just a flow control component. When it is placed inside a safety circuit, the valve becomes part of the system’s risk control logic. Whether the application involves pneumatic motion, hydraulic pressure isolation, or emergency shutdown, the valve’s failure behavior directly affects personnel safety and equipment protection.

Unlike ordinary industrial solenoid valve applications, safety circuits require engineers to think beyond normal operation. What matters most is how the valve behaves when something goes wrong. Power loss, internal sticking, and seal degradation are among the most common failure modes, yet they are often underestimated during selection.

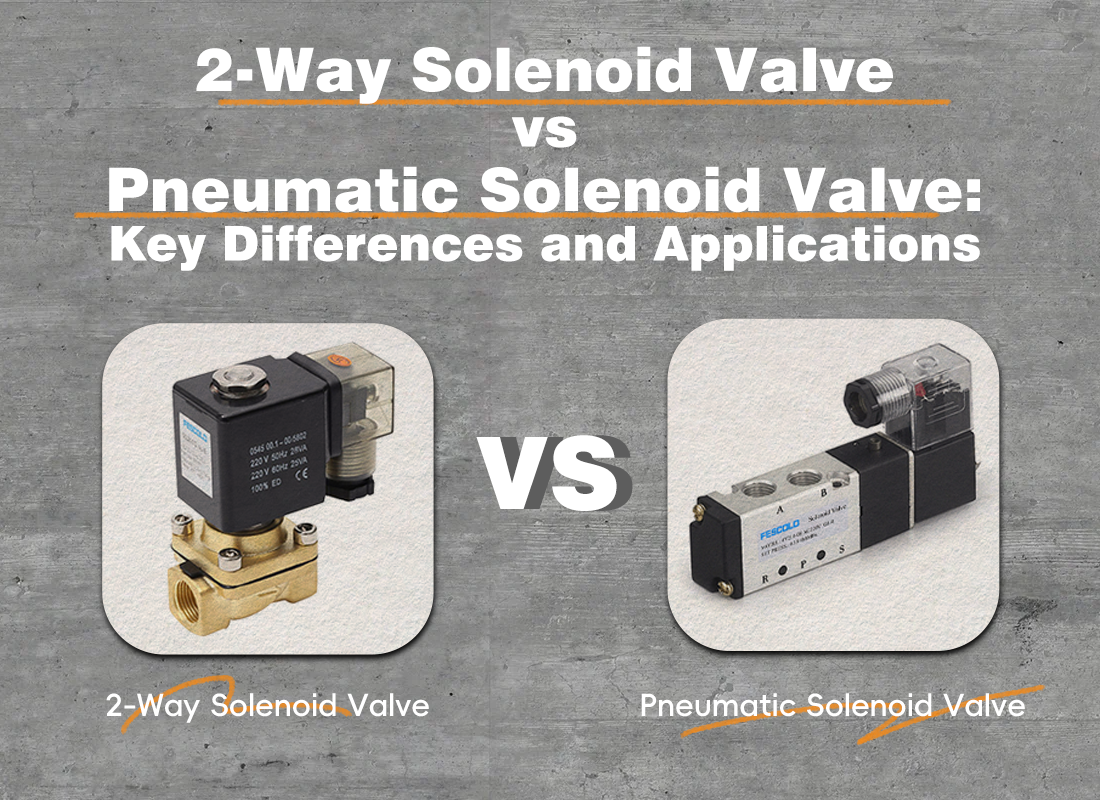

A solenoid valve 2 way design is widely used in safety systems because of its structural simplicity and predictable flow path. With only one inlet and one outlet, the valve either allows flow or blocks it completely, making system behavior easier to analyze under fault conditions.

In pneumatic safety loops, a pneumatic safety valve is often expected to vent pressure rapidly when de-energized. In hydraulic systems, hydraulic solenoid valve safety relies on tight shut-off to prevent uncontrolled actuator movement. In both cases, engineers commonly prefer normally closed solenoid valve configurations so that flow stops automatically when power is removed.

This preference reflects a broader design principle: safety should not depend on active energy input.

Among all solenoid valve failure modes, power loss is the easiest to anticipate. When electrical supply is interrupted, the solenoid coil can no longer generate magnetic force, and the valve returns to its default position through spring force or system pressure.

For a fail safe solenoid valve, this behavior is intentional. In safety circuits, de-energization should lead the system into a known safe state, such as pressure release or flow isolation. A normally closed 2 way solenoid valve, for example, immediately blocks flow when power is lost, preventing further energy transfer.

However, problems arise when the valve’s default state does not match the safety logic of the system. Selecting the wrong configuration can turn a predictable failure into a hazardous one.

While power loss is binary, mechanical sticking introduces uncertainty. Inside 2-way solenoid valves, the plunger or spool must move freely within tight tolerances. Contamination, corrosion, or lubricant breakdown can increase friction and slow down response.

In safety circuits, even a short delay can be critical. If a valve sticks during an emergency stop, pressure may remain in the system longer than expected. This is especially risky in high-cycle industrial solenoid valve applications, where repeated switching accelerates wear.

Engineers often overlook this risk when focusing only on electrical ratings. In reality, filtration quality, air dryness, and material compatibility are equally important in preventing spool sticking.

Seal performance determines whether a safety circuit solenoid valve can truly isolate energy. Over time, elastomer seals harden, shrink, or crack due to temperature, chemical exposure, or pressure cycling. This aging process does not usually cause sudden failure but leads to gradual leakage.

In pneumatic systems, seal aging may prevent full depressurization. In hydraulic circuits, internal leakage can allow actuators to creep even when the valve is nominally closed. Both scenarios undermine the safety function of the valve without triggering immediate alarms.

Selecting appropriate seal materials and planning regular replacement intervals is essential, especially for valves expected to remain installed for years without maintenance.

Although the basic structure of a 2 way solenoid valve remains similar, failure consequences differ between media. Pneumatic systems are compressible and more forgiving, but delayed venting still poses safety risks. Hydraulic systems, by contrast, store energy at much higher densities.

In hydraulic solenoid valve safety design, internal leakage caused by seal wear can translate directly into uncontrolled motion. This is why hydraulic safety circuits often combine solenoid valves with mechanical locking or pressure monitoring devices.

Understanding these differences helps engineers avoid applying pneumatic assumptions to hydraulic systems, where margins for error are much smaller.

| Failure Mode | Primary Cause | Safety Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Power loss | Electrical interruption | Valve returns to default state |

| Spool sticking | Contamination, corrosion | Delayed or incomplete switching |

| Seal aging | Heat, chemicals, cycling | Leakage, loss of isolation |

| Coil overheating | Overvoltage, duty cycle | Reduced magnetic force |

This comparison highlights why solenoid valve failure modes must be evaluated as a system, not as isolated component issues.

When specifying 2 way solenoid valves for safety circuits, engineers should evaluate more than port size and voltage. Default position, material selection, contamination tolerance, and maintenance accessibility all influence real-world safety performance.

For distributors and OEMs, recommending a fail safe solenoid valve configuration aligned with the customer’s safety logic adds long-term value. For end users, understanding how normally closed behavior, seal materials, and response time interact can prevent costly retrofits later.

Safety circuits do not forgive assumptions. Every component, especially a solenoid valve, must fail in a way the system expects.

(FK9025)

Fluid Retention During Supply and Exhaust Switching in 3-Way Solenoid Valves

Fluid Retention During Supply and Exhaust Switching in 3-Way Solenoid Valves

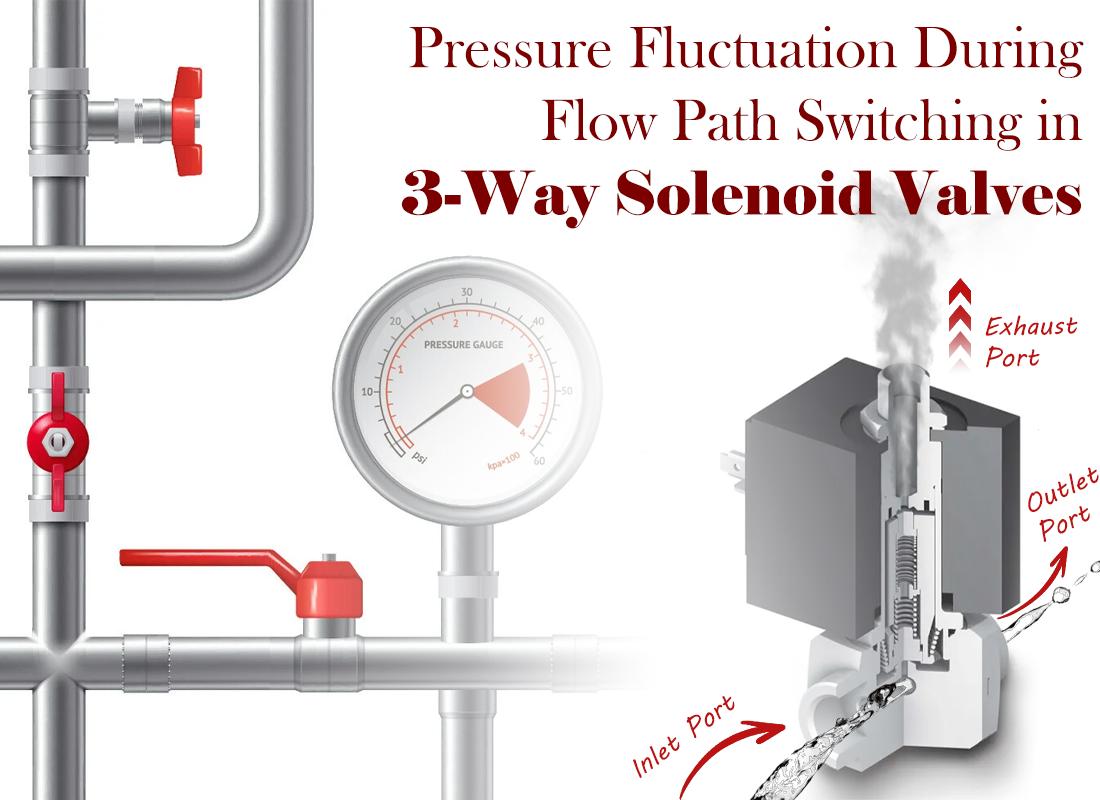

Pressure Fluctuation During Flow Path Switching in 3-Way Solenoid Valves

Pressure Fluctuation During Flow Path Switching in 3-Way Solenoid Valves

Control Characteristics of 2-Way Solenoid Valves in Intermittent Liquid Supply Systems

Control Characteristics of 2-Way Solenoid Valves in Intermittent Liquid Supply Systems

Impact of Contaminated Media on 2-Way Solenoid Valve Cores

Impact of Contaminated Media on 2-Way Solenoid Valve Cores

2 Way Solenoid Valve Performance Differences in Gas and Liquid Media

2 Way Solenoid Valve Performance Differences in Gas and Liquid Media

You May Interest In

Dec 31, 2025 Blog

Pneumatic Solenoid Valve Manual Button Explained

FOKCA ©1998-2025 All Rights Reserved Sitemap